Trying to piece together the early history of firearms is a challenging business. We know that arquebuses were used in warfare from the later fifteenth century. However, few of these everyday weapons survive. The guns that we have from the sixteenth century are typically the luxurious presentation weapons given to courtiers and princes. Yet thanks to a grant from the Arms and Armour Heritage Trust in 2019 I was able to spend the months of February and March visiting a series of northern Italian archives to comb through their sources and try to put these artefacts in context.

Although individual archives often have substantial gaps in their records, by combining information from inventories of weapons taken by multiple Italian states we can discover a great deal about trends in arms ownership. The dukes of Ferrara, Parma and Florence all kept records of weapons held in their armouries, and in times of war surveys of wider arms ownership were sometimes taken in order to assess the state of civic defence. I spent two weeks in Florence surveying material in the archive of the Medici dukes of the city, focusing in particular on references to firearms in their wardrobe accounts, as well as examining material in the archives of earlier republican governments covering the purchase, maintenance and distribution of firearms. This along with day trips to the archives in Modena (for the dukes of Ferrara) and Parma, has given me a comprehensive picture of firearms ownership in the sixteenth century across the three ducal courts, as well as more fragmentary material for comparison on wider arms ownership and use.

For peacetime, gun licences, along with decrees on the licensing process and wider regulations around gun ownership and use, help us understand how governments tried to limit the misuse of firearms while still ensuring they could be used for legitimate purposes of self-defence and civic protection. And when people were caught misusing guns, that could lead to a police investigation: witness statements from these proceedings often shed a great deal of light on the ways guns were used, misused and more generally thought about in the sixteenth century. These were the key areas of focus for my research in the Archivio di Stato di Bologna, which has excellent surviving series of criminal records as well as legal documentation. I spent four weeks here, splitting my time between the Bologna archive and day trips to consult material in Modena and Parma.

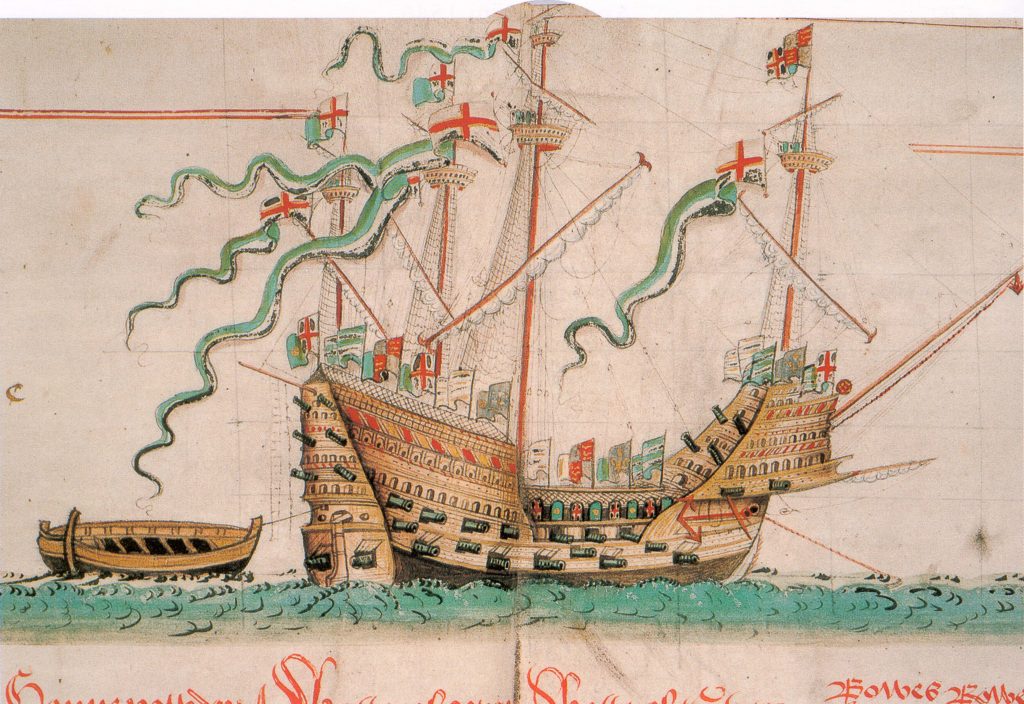

All these centres all connected in different ways to arms producers in Gardone Val Trompia, outside Brescia, an important gun production area in the sixteenth century and indeed today. The firearms produced by Gardone artisans were used not only by the Venetian army and navy (the area was under Venetian rule), but also exported to many other European rulers, including Henry VIII. I therefore decided to spend two weeks in Brescia, following up connections to a range of records produced by both the city’s ruling officials and also members of its aristocratic families, as well as a number of rare books held in the city’s library which provide vital clues to the best approach to take in this archive research. The official export licences now held in Brescia’s state archive reveal not only who was allowed to purchase these guns, but also how many they were able to obtain in practice, illustrating some of the challenges of matching supply with demand. Together with account books and letters these documents reveal a great deal about the process of arms purchase, while legal documents in the Brescian archives also provide clues to the ownership of arms production facilities.

Over the course of my eight weeks in the archives I was able to consult material from no less than thirty-seven different archival units in Bologna, eighteen in Brescia, twenty-six in Florence, fifteen in Modena and four in Parma. I returned to the UK with over 3,300 photographs of relevant documents for analysis, and expect to produce a minimum of three major journal articles for academic publications based on these resources. I will also be submitting a grant application to fund a team of people to develop the work on a larger scale.

My first two research articles from this project are about to be submitted, and I’m always happy to talk to local history groups about my work as well as to receive enquiries from fellow researchers. You can get in touch via my website at www.catherinefletcher.info.

Professor Catherine Fletcher

Manchester Metropolitan University